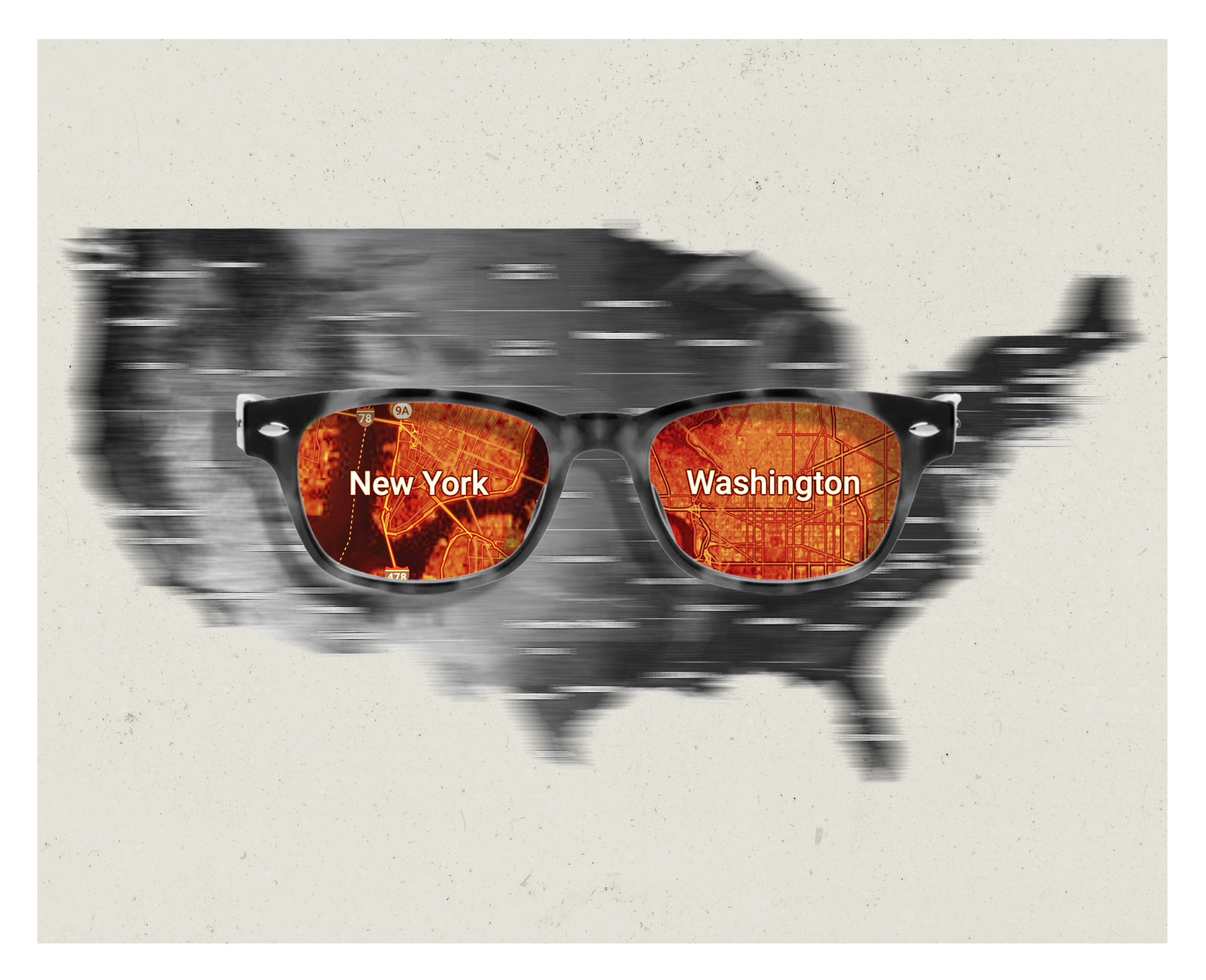

In all the lacerating postmortems on what the media got wrong in covering the 2024 election, one of what should be the most salient questions is largely being ignored: If the major national news organizations are all based in Manhattan and DC—where Kamala Harris racked up 81 and 90 percent of the vote, respectively—how can they possibly reflect the concerns of the rest of the country?

No matter how hard we try, confirmation bias has to influence where our imaginations and curiosity can go; it’s the way the human mind works. If all the campaign buttons, T-shirts, lawn signs, and friends and family around you favor Harris, and if you and your peers have college degrees and are getting by economically, and if your inbox is filled with newsletters written by people whose views mirror your own, can you really think differently about what the country looks like to a majority of Americans? If almost everyone in the newsroom, including its leaders, thinks alike, how can different understandings emerge in their work?

Attempted workarounds don’t seem to have helped much. This time around, some news organizations sent a few more correspondents to those mysterious rural and suburban locations, almost all red on the electoral map. Some set up focus groups to hear from people outside the big coastal cities. Some pledged, as they did in 2020, to emphasize, or at least allow, more diversity of background and thought on their staff. Anecdotally, the latter appears, for the most part, not to have happened.

The problem, I think, isn’t that coastal big-city news organizations aren’t aware of their challenges and aren’t trying to address them. The problem is that they are big-city coastal news organizations and, though they can improve to some degree, they are always going to be driven by their nature. Their myopia has only been exacerbated over the past couple of decades, as declining resources led to the wholesale closing of domestic bureaus.

Short of packing up and moving, what can these elite newsrooms do to engage more directly with the rest of the nation?

They need first to understand that the fragmentation of media, despite its adverse—and arguably disastrous—effects, ironically opens the door to possible solutions. Local, independent, and niche media, spread throughout the country, can offer a revealing window on their communities and, sometimes, even on national issues and the national mood. They have done amazing work this past year. We wouldn’t know about astonishing corruption and abuse by Mississippi sheriffs over two decades if not for the intrepid reporting of Mississippi Today. We wouldn’t know about poor healthcare and neglect in Maine’s residential care facilities, and the state’s ineffectiveness in reining in these abuses, without the independent, nonprofit Maine Monitor, in partnership with ProPublica. It was the hyper-local North Shore Leader that broke the story of George Santos’s lies and corruption well before he was elected to Congress. And on and on. That kind of record makes supporting and funding such local nonprofits absolutely essential.

In addition, national news organizations should rely more on local media for local coverage, establishing true partnerships in which the work of the local outlets is respected and embraced. Such partnerships of equals—with the locals treated not as stringers and fixers but as true colleagues—are the best antidote to the deficiencies of parachuting into unfamiliar environments. It’s time for more news organizations to conceptualize and build local partnership models, as TV networks often maintain with their affiliate stations. And, when they can, the big players should help support these local newsrooms, as the Associated Press is doing as it works to raise money to fund and support local journalists who don’t work directly for AP.

It helps to have a national perspective, and it helps to have local knowledge—you need both. As a local reporter in my very first job, I was sometimes on the receiving end of condescension—and story theft—from national correspondents who were sure they knew better because they came down to Tampa and Tallahassee from New York and Washington. They got a lot of things wrong. Unfortunately, when I started working in New York, I didn’t take that lesson with me initially. I did some parachuting of my own—whether to Bhopal, India, or South Bend, Indiana—and I still wince at all the misinformation and bias I brought into town.

It will remain challenging for major news organizations to gain clarity about this complex nation as long as their leaders, and so many of their journalists, go to work each day in the places where people like myself hang out. It’s time that they reach out for help and guidance from journalists who live and work someplace else.

Have additional thoughts? Think we’re missing something? Email us to keep the conversation going.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Columbia Journalism Review.