October 15, 2024

Audience transparency in the final weeks of election season, new AI guidelines for documentary producers, navigating Springfield misinfo.

This summer, when “Robert,” an anonymous source with alleged ties to Iranian hackers, provided reporters at New York Times, The Washington Post, and Politico with internal Trump campaign documents, the newsrooms all declined to publish any of their contents. At the end of September, Judd Legum, the publisher of the journalism newsletter Popular Information, shared that he had received additional Trump campaign and legal materials from “Robert,” dated as recently as Sept. 15, but had no intentions to publish them. Then, on Sept. 26, Ken Klippenstein, former reporter for The Intercept and The Nation, took the leap, publishing a leaked 271-page dossier compiled by the Trump campaign on vice presidential candidate J.D. Vance in full to his 75,000 Substack subscribers.

The decision of major outlets not to publish, in some cases without any clear explanation as to why, raised immediate ethical questions. These news organizations and countless others had published detail after detail from emails between Hillary Clinton and John Podesta, chairman of her campaign for president, that had been made public by Wikileaks after a Russian hack in 2016. Why the change of heart in the 2024 election year? Was the press giving a break to Trump, or had newsrooms learned a lesson from their earlier publication of Clinton’s emails, or was the Robert trove simply less newsworthy than the Clinton trove?

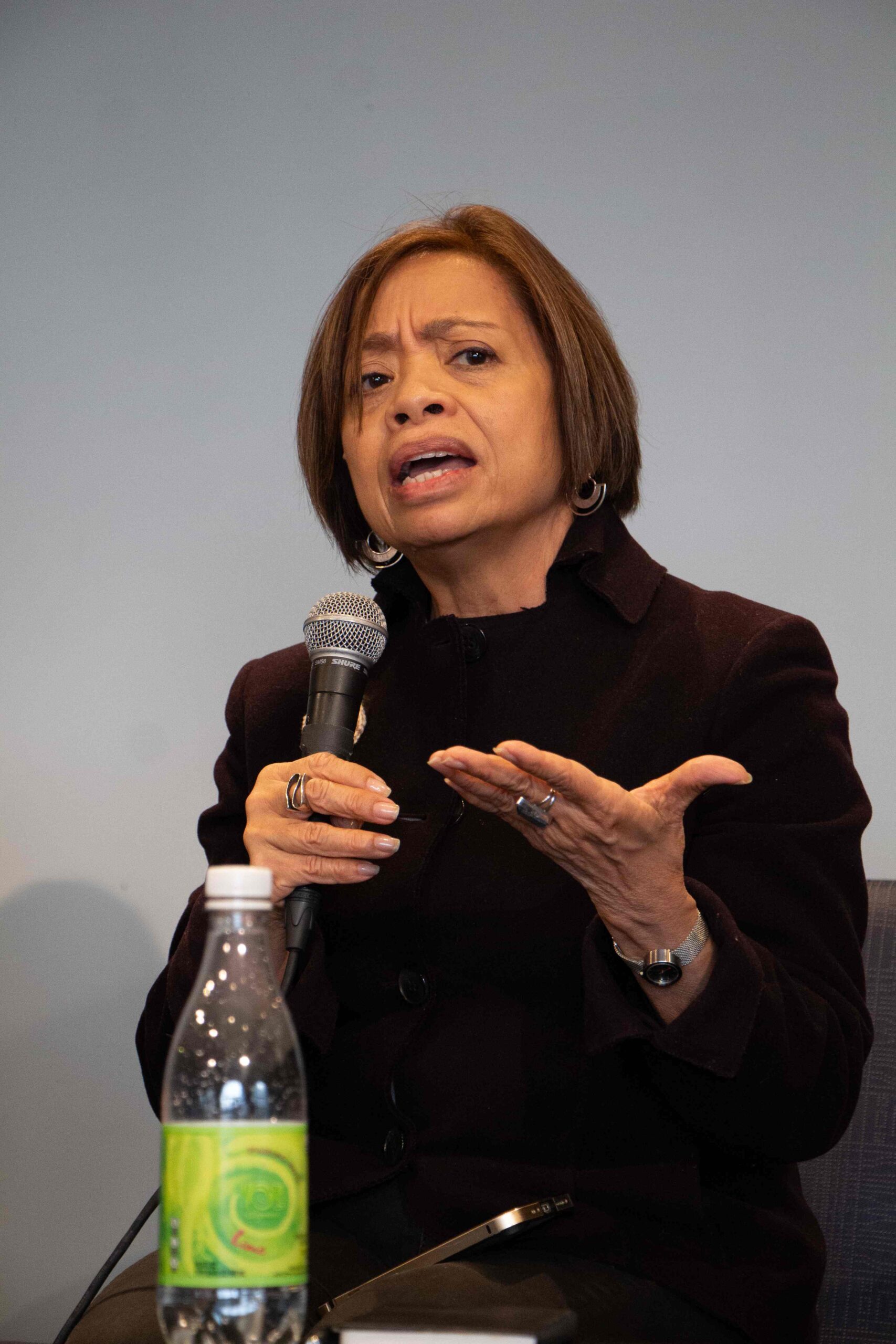

Media-commentary heavyweights, from Margaret Sullivan to Dick Tofel to Ben Smith, have weighed in on these issues in their writings and in a panel discussion at the Ethics & Journalism Initiative at New York University last month. At the panel, Smith and veteran newsleaders Kathleen Carroll and Sewell Chan debated ethical considerations at play in deciding whether or not to publish hacked materials, from verifying document authenticity to weighing source motivation, newsworthiness, national-security interests, and past behavior. (Read our full event takeaways here).

All panelists, however, emphasized an additional ethical issue that persists regardless of newsrooms’ decision to publish: audience trust and transparency. Newsroom leaders and media commentators aren’t the only stakeholders in this conversation. Audiences deserve to know why a news organization won’t publish information it has in hand, especially in a high-profile instance such as that created by the Robert leak.

The majority of readers aren’t party to the debates occurring in tight media circles nor are they primed to give us the benefit of the doubt, assuming well-reasoned, ethical decisions or a reckoning with past failures. Reporters and editors decide not to publish information all the time without comment, and it is important that outlets preserve that discretion. But in the case of a highly publicized story unfolding during an influential presidential election, it shouldn’t be surprising that the perceived decision to change course has invited charges of double standards, hypocrisy and media bias, secrecy, and collusion.

Debunking these accusations is central to assuring audience trust in the final months leading up to the election, and they warrant a response more permanent and accessible than a passing reference in a news article or podcast. As Trusting News writes, “[Transparency elements] can help satisfy the audience’s interests while also potentially filling an information void for someone that could have instead been filled with an assumption (normally negative).” Recent on-the-record interviews, like Paul Farhi’s with New York Times editor Joseph Kahn for Vanity Fair, are promising, but more robust, standing explanations and context offered by the outlets themselves within articles about the hack or broader election coverage will contextualize reporting and reach skeptics now and in the future.

U.S.-based reporters, photographers and video journalists face unique ethical challenges as foreign correspondents. Join Ethics & Journalism Initiative Director Steve Adler and three distinguished panelists: Pulitzer prize-winning correspondent Azmat Kahn, photojournalist Victor Blue and former New York Times “fixer” Martha Metaferia on Monday, March 10, at 12 pm for lunch and a panel discussion of such issues as parachuting in to cover international disasters; using local reporters as fixers; and navigating the danger of identifying oneself as a journalist. The event is co-sponsored by the Overseas Press Club of America.

To learn more about the award and the application process, please see our Submission Guidelines or email Project Manager Ryan Howzell with any questions.

Emiliana Sandoval, managing editor for standards at the education nonprofit Chalkbeat, tells a couple of stories to explain why Chalkbeat’s code of ethics calls on reporters to “use special sensitivity” when they write about students.

In one instance, Sandoval said, Chalkbeat ran a feature about an American community rallying around a family of seven siblings who had arrived in the U.S. from an African country without their parents. The oldest of the siblings was 21 and agreed that he and his brothers and sisters could be quoted by name in Chalkbeat’s story and depicted in a family photo that accompanied the piece. But about six years later, Sandoval said, one of the younger sisters contacted Chalkbeat to ask that her name be removed from the piece. She told Chalkbeat that she’d been too young, at the time, to understand all of the implications of her family’s public exposure. Chalkbeat, Sandoval said, agreed to remove a quote from the sister.

In the second incident, a parent whose child had been featured in a Chalkbeat story about services for disabled students reached out with an unusual request years after the piece originally appeared. The parent, who had agreed to be quoted by name in the story, had no problems with the article, Sandoval said. But the child, now old enough to find the story in a Google search, was worried about being identified as disabled whenever anyone searched for their name and found the article. Chalkbeat, Sandoval said, ended up changing the child’s first name in the piece.

What those anecdotes show, Sandoval said, is that the standard ethical practice of obtaining consent from a parent or guardian before identifying a child, may not suffice when you’re writing about vulnerable kids. (Or teachers, for that matter, but that’s a different story.)

“We’ve been more protective in the last few years,” Sandoval said. “We are really intentional about not doing any harm, especially with students.”

For the new standards Chalkbeat has implemented in response to these stories, read the full article at ethicsandjournalism.org.

We’re still buzzing about our “Lunch & Learn” workshop last week on ethical and legal considerations for student journalists when covering their own campuses.

The in-person and livestream event attracted student reporters from across the country, many of whom have stepped in to cover some of the biggest campus news stories from student protests to curriculum clashes and high-profile leadership resignations over the last eighteen months.

Our panel was moderated by Stephen Solomon, Marjorie Deane Professor of Journalism and founding editor of First Amendment Watch, and featured Stephen J. Adler, Ethics & Journalism director; Sheila Coronel, director of the Toni Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism at Columbia University; and Yezen Saadah, editor-in-chief of NYU’s own Washington Square News.