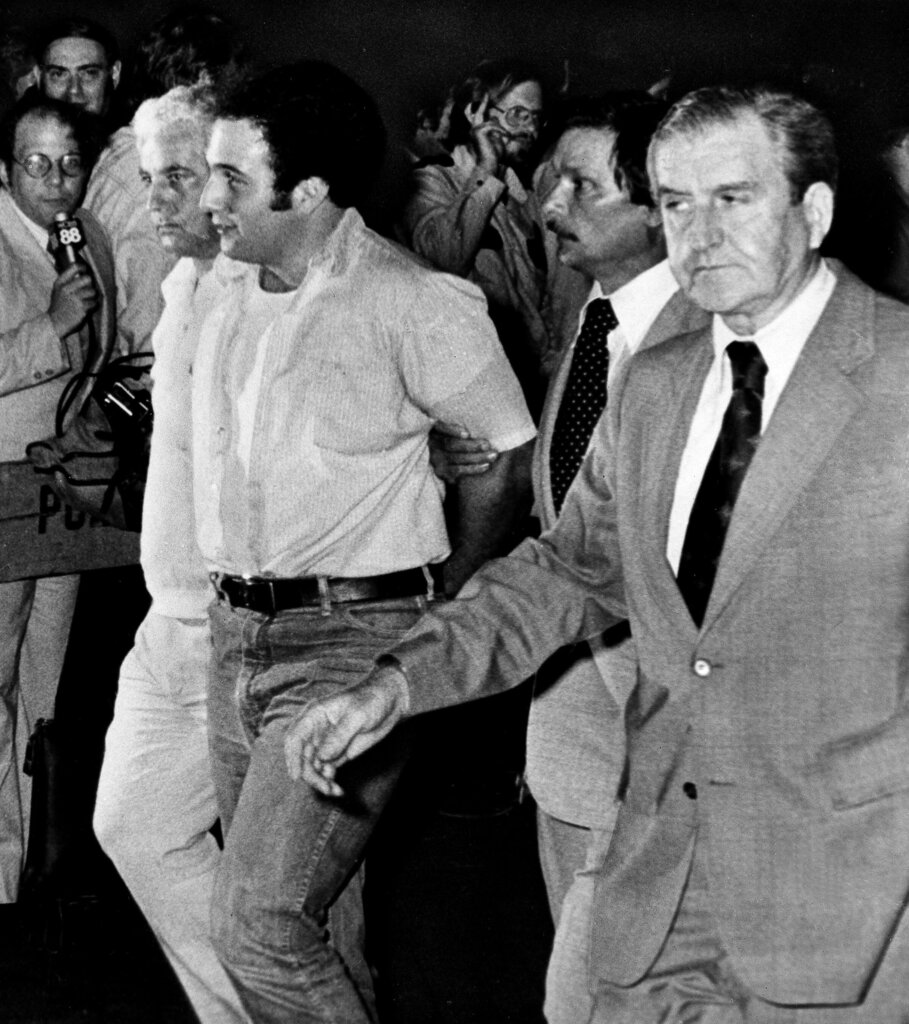

No one looks innocent when photographed standing against the wall at a police station for a mugshot or being escorted in handcuffs by a bevy of law enforcement officers in a so-called perp walk. As The New York Times noted in a 2018 retrospective on perp walks, even Mother Theresa would look shady under such circumstances.

Mugshots and perp walks have nevertheless been a staple of news coverage for decades. It’s hard to resist when law enforcement sources tip your newspaper or television station about splashy arrests so reporters can be on site, cameras ready, to witness a high-profile defendant being hauled into custody. And for resource-strapped newsrooms, it’s cheap and easy to illustrate crime stories with mugshots distributed by police departments and sheriff’s offices.

Some newspapers in the early 2000s took full advantage of these free photos, driving web traffic by publishing mugshot “galleries” or “carousels” of booking photos obtained from law enforcement.

But that practice has begun to change over the last eight or 10 years, as news organizations started to weigh the harm of these incriminating images against their news value. The defendants portrayed in mugshots, after all, have been arrested but not convicted, so they are presumptively innocent. Yet in the digital age, if their booking photos are published, these damaging images will forever haunt them on the internet.

Moreover, as Poynter and The Marshall Project reported in a 2020 article about changing attitudes toward the publication of mugshots, these photos – especially when they are presented in a gallery of images – tend to reinforce biases about who commits crimes. An advocate for formerly incarcerated people described a vicious circle, in which the routine publication of mugshots can reinforce the perception that people of color disproportionately commit crimes, increasing the likelihood that defendants will be arrested and convicted.

A more ethical approach is the policy adopted by The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2020. The Inquirer does not entirely prohibit the publication of mugshots. But it limits their use to cases involving public figures, notorious crimes or public safety.

“If there is a compelling and immediate public safety reason to publish a mugshot, we will do so. These uses will be rare,” the Inquirer code says.

News organizations including Gannett, AP, the Chicago Tribune, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Houston Chronicle, and the Radio Television Digital News Association have all adopted similar policies, discouraging or prohibiting the routine publication of mugshots, particularly for minor offenses. Those policies coincide with recent legislation in states including New York, Illinois, and Utah that restricts law enforcement agencies from distributing booking photos of defendants who have been arrested but not convicted.

The National Trust for Local News last year adopted one of the most thoughtful approaches we’ve seen to mugshots, as part of its broad rethinking of crime coverage by the 30 or so newspapers under its umbrella. The Trust flat-out bars the publication of mugshot galleries or carousels. It also says mugshots should not be used as the main illustration on a story, urging news staff to seek out alternative images, such as courtroom photos.

The policy does permit the publication of mugshots, after internal discussion, in cases “where public safety is at risk, the suspect is prominent, the crime is a felony and of significance, and/or the public value of publishing the mugshot outweighs the potential harm.”

There is always going to be public interest in mug shots and perp walks. Audiences are attracted to the spectacle of public shaming. But journalists should think hard about whether they’re doing more harm than good – to both story subjects and readers – by indulging that impulse.