Henry Luce is sometimes given credit for solidifying the separation of church and state in American journalism, with his insistence on a wall between editorial and business functions at Time Inc. publications. He didn’t come up with the idea, though—in 1869, literary critic Richard Grant White was already declaring that “nothing in the interests of an advertiser, no matter what his importance, shall be admitted into the editorial columns for any consideration.” Nor was Luce as much of a purist as his reputation might suggest. Not only was he, perhaps ironically, editor and executive at the same time, but he also said that, “If we have to be subsidized by anybody, we think that the advertiser presents extremely interesting possibilities.” He knew no newsroom can exist without a business side, and in fact he went on to say that, while he only wanted to compromise a tiny bit of integrity, a “small fraction of our journalistic soul” he would happily sell.

Today, in my role as managing editor at TIME, Luce’s flagship publication, I think every day about how to coordinate between the editorial department and our colleagues on the business side in a way that both supports our company and protects our integrity. The question often presents as a logistical one (about who should get access to which Airtable, for example), but its urgency has never been clearer. It’s not news that ours is a moment of precarity for the news business, in terms of both finances and trust—an era when most Americans believe that most news outlets are primarily motivated by their own monetary interests. And so, as part of the 2024 cohort in the Executive Program in News Innovation and Leadership at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, I took a look at the state of “the Wall” and where things stand in terms of best practices for a workable vision of its future.

I conducted an informal survey of industry professionals and interviewed a number of current and former newsroom leaders, and found that a whopping 86.1% of my respondents reported observing that the relationship between business and edit has changed over the course of their careers. Independence is much more rare “and I hate that for literally everyone,” said one. At the same time, some welcomed the change, believing a closer relationship across the divide is healthier. “Much more collaboration than in the past,” wrote another. “But still not nearly enough.”

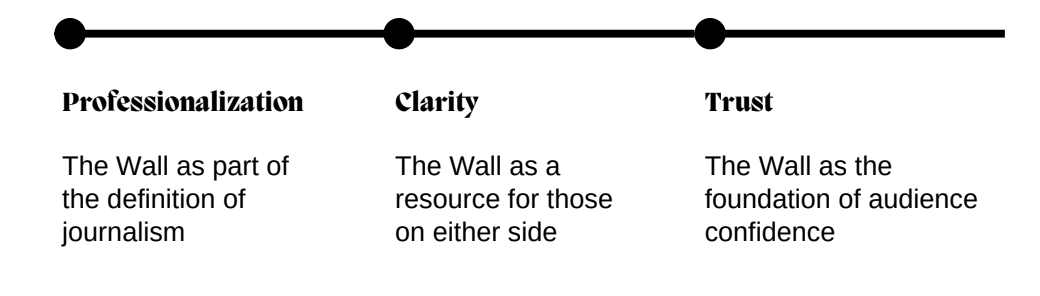

About a third of my survey respondents knew of someone in their organization whose job is expressly to be the liaison between the two sides, and more than half have a regular meeting at which coordination across the division occurs. But no matter how that communication happens, it was clear that some of the most important functions of the old-fashioned wall need to be preserved. After all, as one former EIC told me in an interview, “trust, of course, is the thing you’re ultimately selling—you’re selling it to advertisers and you’re selling it in subscription costs.”

My research turned up several key ways different outlets are working to maintain that trust, ranging from the creation of a separate department dedicated to communication between sales and edit to the publishing of reader-facing disclosure policies. While the tactics may differ in the details, many industry professionals share a consensus on the importance of having a thoughtful approach and communicating about it effectively.

Henry Luce also said that there’s “not an advertiser in America who does not realize that Time Inc. is cussedly independent.” He knew that that awareness, from advertisers and audiences alike, was what made it possible to sell what he was selling. The same goes for our industry today, if we want to continue to produce the journalism our world so desperately needs.